Tunneling the The Tunnel

What is it about large books that makes them subject to a different, more tactile sort of scrutiny? Is it that their girth lends them to be regarded as objects more than a thin volume which seems to depend on its neighbors to physically and culturally keep them upright? Or is it, in their ponderous length, we can’t possibly assimilate or manage the entirety of their content across the passage of time in our own lives, and thus need the shape of the book itself to become a kind of synecdoche for the text?

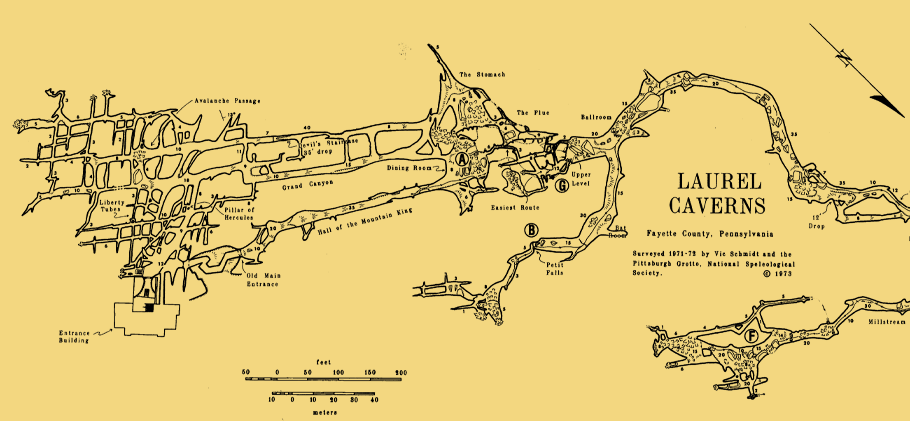

I don’t often read large books. The last was LA MEDUSA by Vanessa Place, maybe 6 years ago. Prior to that, MOBY DICK, perhaps 9 years ago… beyond that, stacks of Bánffy, Mann, and Proust sprinkled over the balance of the last 20 years. I had looked forward to reading William Gass’s THE TUNNEL for a very long time. It’s had an aura of sorts. I’ve only otherwise read OMENSETTER’S LUCK by Gass. I did not care for it… to the extent that were it any other writer I never would bother picking up another of their books. Why lust after THE TUNNEL? I hate to tell you that it has to do with the tasteful thickness of it. The metaphorical conceit–in my mind only–of a brick of bound paper and all associated metaphiers of tunneling was a fascinating way to think about a book::: The text itself, the book I mean, is a spatial construct through which the reader passes. The book, the physical paper thing, is tunneled into by some collection of key points constructing a worldline. The book, reproduced around the world, identical copies, create a circuit of opportunities, troglodytic readers encountering one another in the depths, curling up together to recite. (I like to picture the speleographic mapping robots in PROMETHEUS constructing a live digital cartography not of the contents of the book, but of the distribution of the aura of the book all across the planet)… All of these things could be the tunnel, could be the possibility of THE TUNNEL and its conceptual underpinnings.

THE TUNNEL is a virtuoso execution. But it was not the book I set out to read. That is neither Gass’s fault nor is it mine.

Sometimes unread is better.

The conceit, instead, is twofold: William Kohler, a historian, has completed his work on the book GUILT AND INNOCENCE IN HITLER’S GERMANY and is struggling to write an introduction. Instead, in Shandean fashion, he spends the entire book distracting himself with reflections on his childhood, marriage, and academia… / …additionally, and minimally, in the fashion of Sterne’s Uncle Toby, Kohler is constructing not a miniature battlefield, but excavating a tunnel out of his basement office, I say minimally because very little of the text takes place in that present, in that basement, in that tunnel.

The tunnel instead, if you suffer my interpretation, is Kohler tunneling back through his life.

I have my own long and boring life to tunnel. I’ve run out of use for the borings of other people’s memory tunnels.

As Philip Channard says, “The mind is a labyrinth.” True! And it is a labyrinth of the mind. Text is not the mind. Text is a labyrinth of a different material. Were the text to be a labyrinth of the labyrinth of the mind, a phase change must occur. It must become material. I don’t believe our thoughts look the way we think they do when transcribed to text.

I want a book inert enough for me to dig a hole in the contemporaneous abstract moment of its soil.

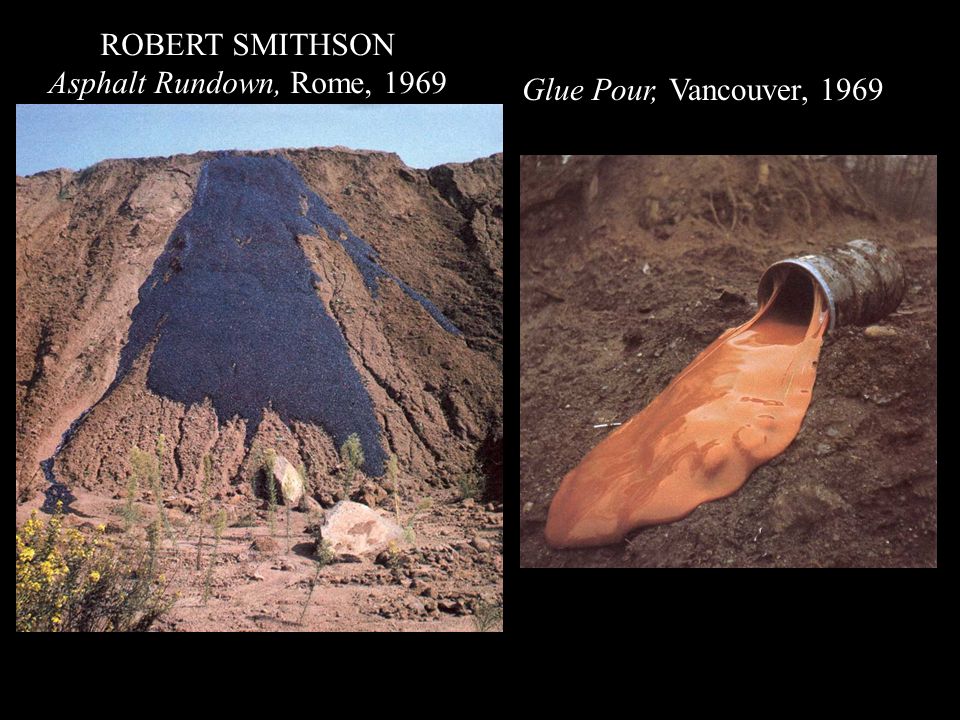

Text is a raw material. It is the thickened possibility of the entirety of culture and industry, latent, percolating there on the page, seeing through to the ink on the verso face of the page, and deeper and deeper, printed on transparency in order to see the entire book at once. A book must be written (by someone/thing). It is full of intention. That origin is inescapable, I’m aware. But then the book comes to me, released by its author, encoded with and structured around that intention. The intention to serve it tartar is very different than the intention to cook it to any level of doneness. Oh & I want it to cook in my tepid mouth.

This can all be found in Umberto Eco’s THE OPEN WORK. None of it is new thinking, although my expectations of the book perhaps derive more from Eco’s writings on Dubuffet’s paintings than on Joyce’s books.

I simply want to spend less time in the author’s head and more in my own. And I am not tremendously consumed with meaning.

I want to stare at the book and see what coalesces in a struggling blur out of the noise of unorchestrated morphemes. A book you can read 3 lines at a time. A book you can read by focusing on the center of the page. A book you can read with your eyes crossed (which I can’t do).

I like a mess. THE TUNNEL is a mess, and yes quite a glorious mess, an incredibly effective mess. But it is Gass’s mess. It’s Kohler’s mess. I know someone has to write the book, I’m aware. But I want the mess to spill out of their container and conform to my topography.

If I were to take control for a moment, and consider perhaps a more fruitful narrative armature off of which to ooze and slop that mess, what I do find potentially interesting to the conceit is the way it brings together two of Nabokov’s middle career works, PALE FIRE and PNIN. I say interesting to the conceit because the potential–the potential I desire, but of course it’s not my book–is not realized. The idea of an introduction to a book we will never read is fascinating… Borgesian, echoes of Milorad Pavic, and of Nabokov’s Kinbote. What might one do with this? Kohler, who we could stand to know far less about–for instance, I don’t need to know how he wipes his ass–could utilize his unreliability to excuse himself for his own relationship to the atrocities while using the book we cannot read, only in reference, to make proxy admissions about himself. He could recount details of the war that are so false that we know he is being disingenuous. Basically, imagine all of the intricacies of PALE FIRE regarding the futility of authorship injected into this context. Secondly, PNIN, although in a similar academic setting to PALE FIRE–and even LOLITA–serves as a wonderful analog to Gass’s takedown of academic futility and intellectual onanism. On that count Gass is successful, not in Nabokov’s satirical fashion, but with a prosaic bluntness that is complicit with the farce, that honestly makes the reader feel quite like shit. (Is cynicism ultimately more optimistic than satire?) Rather, if coupled with the unreliability of my imagined version of Kohler’s introduction, the doofus Pnin’s impotence and impishness might doubly cause the reader to reconsider the errors as Pnin-being-Pnin and not nefarious or evasive.

I still love the tasteful thickness of THE TUNNEL. It is a book that has a presence, a mystique, and when I look at it on my shelf I do well to replace my disappointment with this inky event–a diagonal “g” trio (immediately upon turning to this page my pupil floated out of my iris, sinking into the copious ink of the two-story g)–in the worldline of my bibliophilia, so ripe with the inertness and graphic potential of the book I didn’t find inside the tunnel.